No More Secrets

An Interview with Peter J. Boni

While the idea of artificial insemination has been around since the 1300s, the first human offspring reported was in England in 1790. But it wasn’t until the 1940s that more than a few hundred women successfully gave birth to what we now refer to as “donor conceived persons” or DCPs. One of the 10,000 born in the 1940s was author Peter J. Boni.

Peter is a successful businessman, CEO of his own company, and the “go-to guy” for assisting high-tech companies in trouble. He is focused, intelligent, driven, and organized, but when speaking with him one-on-one I found him extremely affable. I could see how his piercing blue eyes could probably make people uncomfortable, but he has an easy smile that makes him approachable.

Peter is a successful businessman, CEO of his own company, and the “go-to guy” for assisting high-tech companies in trouble. He is focused, intelligent, driven, and organized, but when speaking with him one-on-one I found him extremely affable. I could see how his piercing blue eyes could probably make people uncomfortable, but he has an easy smile that makes him approachable.

In the early days of donor-assisted conception, some practitioners mixed fresh sperm from the donors was combined with the sperm from the husband and told the couple that it would boost the fertility of the husband’s sperm, thus increasing the husband’s psychological ownership of the pregnancy. But it was all a head-fake according to Peter. His own father had been told he was sterile, so his parents knew with certainty that Peter was not his father’s biological son. While this was not the cause of his father’s depression, Peter wondered if it exacerbated his mental deterioration, eventually leading to his suicide, which in turn added to Peter’s feelings of inadequacy. One of the biggest reliefs for Peter when he found out he was donor conceived, was that he no longer had to fear the specter of his father’s mental illness.

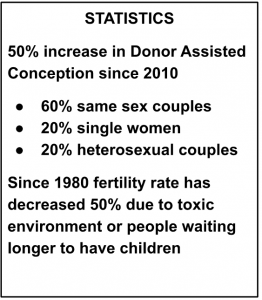

For parents of Donor Conceived Persons from Peter’s generation, there is a strong tendency toward secrets and the need to keep the origins of their children’s conception under wraps. He did not learn until he was nearly 50 that he was donor conceived. After his mother had a postoperative stroke, she let her secrets spill, accidentally. And while it took him a while to forgive his mother for her secrets, he eventually worked through his anger and the trauma he carried – not only from the identity crisis that his discovery triggered, but new trauma always rekindles old trauma that was not dealt with – and Peter carried trauma from his childhood and his father’s suicide, and from his service in Vietnam. “Forgiveness is key”, he says. These days, there is a tendency for parents to be more open with donor-conceived children about their origins – especially children of same-sex couples. They grow up more adjusted to the fact that they are donor-conceived, “it’s in their woodwork”. They are not angry, unlike donor-conceived offspring of previous generations whose conceptions were shrouded in secrecy until a direct-to-consumer DNA test ripped the skeletons out of their closets.

Peter believes in the Donor Conceived Bill of Rights and is hopeful that more states will pass legislation such as Colorado’s. He states he is all for science, but consideration has to be given to the children. He believes that anonymity needs to be abolished and that DCPs have access to genetic and health history information, as well as the restriction to the number of offspring, and a sibling registry – to prevent siblings from accidentally dating, “let’s face it, smart kids go to the same schools”, he says, as well as counseling for both the donor and the parents-to-be. “Donors need to understand that they will be found.”

When discussing fertility fraud, Peter is quick to point out that his conception was not fertility fraud and he believes in legal penalties for those doctors who are guilty of it. His donor story is fascinating. He is 1 of 6 offspring from his donor, an engineer who was friends with American Behavioral Psychologist, B.F. Skinner. The theory among Peter’s sibling group is that his donor, who had two children from his marriage and 4 donor-conceived offspring, may have been recruited as a donor for the Harvard University program by Dr. Skinner.

Peter believes three things helped shape the man he is today: his dysfunctional and disruptive childhood taught him adaptability, his combat and special ops experience shaped his collaborative leadership style, and his college education opened doors of opportunity. Peter decided to write his story for two reasons: his research led him to want to write a tell-all expose about the industry, and he also wanted to write a deeply personal memoir to share his story with others. His story, and his struggles with his identity, resonate not only with others in the DCP community but with those who are Not-Parent Expected (NPE) or Late-Discovery Adoptees (LDA).

In an experiment conducted in the 1950s by Johns Hopkins professor Curt Richter, white mice were thrown in a tank of water and rescued just before drowning. After they recovered, they were placed back into the water, where they spent more time swimming before eventually giving up – because they had learned the situation was not hopeless. For humans, when we know there is hope for survival, we persevere, and hope is what Peter wanted to give people by relaying his story.